Since the Big Bubble popped in 1929, life in the United States hasn’t been the same. Hotshot wizards will tell you nothing’s really changed, but then again, hotshot wizards aren’t looking for honest work in Enid, Oklahoma. No paying jobs at the mill, because zombies will work for nothing. The diner on Main Street is seeing hard times as well, because a lot fewer folks can afford to fly carpets in from miles away.

Jack Spivey’s just another down-and-out trying to stay alive, doing a little of this and a little of that. Sometimes that means making a few bucks playing ball with the Enid Eagles, against teams from as many as two counties away. And sometimes it means roughing up rival thugs for Big Stu, the guy who calls the shots in Enid. But one day Jack knocks on the door of the person he’s supposed to “deal with”—and realizes that he’s not going to do any such thing to the young lady who answers. This means he needs to get out of the reach of Big Stu, who didn’t get to where he is by letting defiance go unpunished.

Then the House of Daniel comes to town—a brash band of barnstormers who’ll take on any team, and whose antics never fail to entertain. Against the odds Jack secures a berth with them. Now they’re off to tour an America that’s as shot through with magic as it is dead broke. Jack will never be the same—nor will baseball.

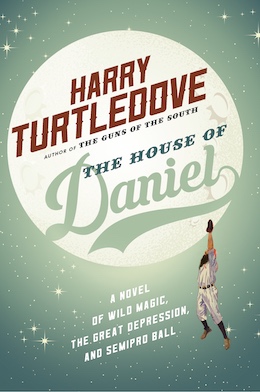

Harry Turtledove’s The House of Daniel, an alternate history novel of magic and minor league baseball, is available April 19th from Tor Books!

I

It would’ve been the first part of May. I remember that mighty well. Spring has a special magic to it. Or spring did once upon a time, anyway. I remember that mighty well, too. But when the Big Bubble busted back in ’29, seems like it took half the magic in the world with it when it went. More than half, maybe. In the five years after that, we tried to get by on what was left. We didn’t do such a great job of it, either.

Other thing the Big Bubble took with it when it busted was half the work in the world. People who had things to sell all of a sudden had more of ’em than they knew what to do with. They tried to unload ’em on the other people, the ones who all of a sudden didn’t have the money to buy ’em. They couldn’t hardly hire those people to make more things, not when nobody could afford the stuff they already had clogging their warehouses.

It was a great big mess. Hell and breakfast, it’s still a great big mess now. And nobody but nobody has the first notion of how long it’ll go right on being a great big mess.

Take a look at me, for instance. Not like I’m anything special. You can find guys just like me in any town from San Diego to Boston. More of ’em in those big cities, matter of fact. But take a look at me anyhow. You may as well. I’m right here in front of you, talkin’ your ear off.

Jack Spivey, at your service. I know too well I’m not extra handsome, but I’m not what you’d call homely, either. I was twenty-four that May, on account of I was born in February of 1910. Old enough to know better, you’d think. Well, I would’ve thought so, too. Only goes to show, doesn’t it?

So there I was on that bright May morning, walking along Spruce Street in Enid, Oklahoma. I didn’t have two quarters to jingle in my pocket. Yeah, plenty like me, Lord knows. Too damn many like me. I wasn’t thinking about much of anything, if you want to know the truth. Maybe wondering how come the leaves on the trees didn’t seem so bright as they had before the bustup, and why the grass looked to be a duller green.

Your hotshot wizards, they’ll tell you things haven’t really changed. They’ll tell you it’s all in your head. What I’ll tell you is, your hotshot wizards weren’t walking down Spruce with me that morning.

The flour mill took up a whole block of Spruce. The mill got built a year before things went to the dogs. Timing, huh? It hadn’t run flatout since. It did still run, though. I’ll give it that much. Some of the jobs the big bosses were bragging about when it opened up were there to that day. Some were—but not all of ’em.

Sure, I’ll tell you what I mean. While I walked by there, a man was rolling a big old barrel of flour to a truck. Only he wasn’t a man. He was a zombie. His face was as gray as the slacks I had on, and just about as shabby looking. No, he wasn’t rolling the barrel very goddamn fast. To tell you the truth, he was rolling it like he had all the time in the world. If you’re a zombie, you do, or you might as well.

But how much do you reckon the rich folks who run the mill were paying him? Right the first time, friend. Zombies work for nothing, and you can’t get cheaper than that. Back when times were good, a colored fella or a sober Injun if they could find one would’ve been rolling that barrel. The rich folks wouldn’t’ve paid him much, but they would’ve paid him a little something.

Now they had colored fellas and Injuns working inside the mill. They never would have before, let me tell you. They pay ’em a little something, but not much. And some of the white guys who would’ve earned more, they were out on the street without any silver to jingle in their pockets and scare the werewolves away, just like me.

Difference between them and me was, I knew how to go about it. I’d been scuffling, doing a little of this, a little of that, a little of the other thing, since before I had to shave. Those guys, they thought they had a job for life. They didn’t know what the devil to do with themselves after it got taken away.

Some of them drank at the saloons across the street from the mill. Anything stronger than 3.2 beer is against the law in Oklahoma. That doesn’t mean you can’t get it, only that it costs more. Even before Repeal, mill hands would drink at those saloons when they came off their shift. Now they were in there at all hours—when they could afford to buy anything, I mean.

Just past the saloons were a couple of pool rooms and a sporting house. The house had to let girls go. That’s how bad things were. It doesn’t get any worse, now does it?

I walked into one of the pool halls. A couple of guys were shooting slow, careful eight-ball at a front table. They looked over when the bell above the door jingled, but they relaxed as soon as they saw it was me. It’s not like I was somebody they hadn’t seen plenty of times before.

Arnie, the guy who ran the joint, he’d seen me plenty of times, too. He hardly moved his eyes up from the vampire pulp he was reading. He was near as pale as a vampire himself—I don’t think he ever went outside. He was wearing a green celluloid eyeshade like a bookkeeper’s, the way he always does.

“How you doing?” he asked me. His voice had more expression than a zombie’s, but not a lot more.

Most of the time, he didn’t talk to me at all. When he did, sometimes it was business. “I’m here,” I answered. “What’s cooking?” Arnie knew people. He heard things.

Like now. “I hear Big Stu’s been asking after you,” he said.

“Has he?” I said. “Obliged.” I touched the brim of my cap—cloth cap, not ball cap. Then I turned around and walked out.

* * *

As soon as I got back on the street, the grass looked greener and the new leaves looked, well, leafier. I’m not saying they were, but they looked that way. To me, they did. Amazing what the thought of some work will do.

It wouldn’t be nice work. You didn’t get nice work from Big Stu. Some people wouldn’t call it work at all. They’d call it burglary or battery or some such name—but Big Stu paid off those people. And he paid the people who did things for him. He paid them good. You can’t be too fussy, not since the Bubble busted you can’t.

Big Stu ran a diner on Independence, near the artists’ gallery. You came in from out of town, you could get the best beef stew between Tulsa and the Texas line. The barbecue was tasty, too. You could get other kinds of things at Big Stu’s diner, but you had to know what to ask for and how to ask for it. You also had to know nothing from Big Stu ever came for free. Oh, yeah. You had to know that real good.

Not many cars, not many carpets, parked on Independence when I headed over to the diner. People didn’t come into town from the country the way they had in boom times. They hunkered down, tried to do without, as much as they could. So did most of the folks who lived in town. I know I did, and I still do—I have to. I bet you’re the same way. These days, who isn’t?

So Big Stu’s joint was like the pool hall near the mill. It had some people in it, yeah, but it wasn’t what you’d call jumping. Big Stu worried about it less than Arnie did, though, ’cause he had the other stuff cooking on the side.

The waitress wasn’t too busy to nod at me. “Hey, Jack. What do you know?” she said.

“I’m okay, Lil. How about you?” I answered. Lil’s about the age my ma would be if she was alive. She uses powder and paint, though. Ma never did hold with ’em. So Lil looked younger—most of the time. When the sun streamed in through the big front window and caught her wrong, it was worse’n if she didn’t bother.

But she had a kind heart, no matter she worked for Big Stu. She set a cup of coffee and a small bowl of stew on the counter. “Eat up,” she said, even though she knew I couldn’t pay for ’em. “He’ll still be in the back when you get done.”

“Thank you kindly” was all I had time for before I dug in. Big Stu’s did make a hell of a beef stew. The bowl was empty—the coffee cup, too—way quicker than he could’ve got grouchy waiting.

I touched the brim of my cap to Lil and went into the back room. You could hold wedding dinners there, or Odd Fellows wingdings— or poker parties or dice games. Those mostly happened at night. During the day, it was pretty much empty… except for Big Stu.

They didn’t call him that on account of he was tall. He had to look up at me, and I’m five-ten: about as ordinary as you get. They called him that because he was wide. His double chin had a double chin. His belly hung over his belt so far, you couldn’t see the buckle. Somebody who ate that good five years after the Bubble popped, you knew he had a bunch of irons in the fire.

I touched my cap to him, too. One of his sausage-y fingers moved toward the brim of his fedora, but didn’t quite get there before his hand dropped again. “Heard you were lookin’ for me,” I said. Big Stu, he never fancied wasting time on small talk.

“That’s right.” All his chins wobbled when he nodded. “You’re headin’ up to Ponca City in a coupla days, aren’t you?”

“Sure am. We’ve got a game against the Greasemen Friday.” Back in those days, I played center for the Enid Eagles. Nobody gets rich playing semipro ball—it’s a lot more semi than pro. But it was one more way to help fill in the cracks, if you know what I mean. Ponca City’s an oil town, which is how come their team got the name it did.

“Okey-doke,” Big Stu said. “Something you can take care of for me while you’re there. Worth fifty bucks if you do it right.”

“Who do I have to kill?” Oh, I was kidding, but I wasn’t kidding awful hard. You can live for a month on fifty bucks. A couple of months if you really watch it.

“Not kill. Just send a message—send it loud and clear. You know Charlie Carstairs?”

“I know who he is.” Everybody in Enid knew who Charlie Carstairs was. Whatever you needed for your farm around there—a plow, a dowsing rod, you name it—chances are you’d buy it from Charlie.

“That’s good. That’s better’n good, in fact. Wouldn’t want you for this if you were his buddy. I did somethin’ for him—never mind what—and now he won’t give me what he owes. So what I want is, I want you to rough up his kid brother in Ponca City.” Big Stu scowled. “I had to put out a geas to find he had a brother there at all. But I did it.” He looked proud of himself then, like a moss-covered snapping turtle soaking up sun on a rock.

“You never sent me out for strongarm stuff before,” I said slowly, which was… close to true, anyway.

He looked at me. He looked into me. He could see more dark places inside my head than even I knew were there. His mouth twisted. A snapper’s mouth doesn’t work that way, but seeing him would make you think it did. “Hell, Jack, a hundred bucks.”

I was still pretty green some ways. I didn’t know I was dickering. He did, or figured he did, which amounted to the same thing. And when he came out with a hundred bucks, why, my conscience spread its wings and flew away. “You’re on,” I heard myself say. “What’s his name? Where do I find him?”

Big Stu didn’t so much as smile. In his way, he was good. “He lives in a boarding house on Palm Street, not far from the city swimming pool. His name’s Mitch.” He reached into an inside jacket pocket and pulled out a scrap of paper. He held it out for me to take. “Here’s the address.”

I had to unfold it. The pencil scrawl read 527 Palm #13. I gave my best try at a tough-guy chuckle. “Lucky number,” I said.

“Lucky for you,” he answered. “He opens the door, you clobber him good before he knows what’s what. Then go to town from there. And then head on over to Conoco Ball Park and get yourself a coupla the other kind of hits.” He laughed.

Well, so did I. I’m not what you’d call proud to admit it, but I did. “I’ll do that.”

Big Stu reached into a different pocket, the one where his billfold lived. He handed me a sawbuck. “Here. Down payment, like. Buy yourself some groceries so Lil don’t ruin my business trying to fatten you up.”

How did he know? Part of his business was knowing things. The door to the back room was shut till I walked through it. So what? He knew anyhow.

I got out of there. The sawbuck felt funny in my pocket. Heavy. Not just a printed piece of paper. Heavy as blood, maybe. What else was it but blood money?

Then I went back to the saloons by the flour mill. No, not to drink up my dividend. I like it fine, thank you, but I hold the bottle. It doesn’t hold me. I was looking for some of the other Eagles, to let ’em know I’d be going over to Ponca City a day early by my lonesome.

Second place I stuck my nose into, there was Ace McGinty, our number two pitcher. He had two, three empty schooners in front of him, and a full one. You got to work to get plastered on 3.2 beer. Ace, he was working. I told him what I needed to tell him. A slow grin spread across his face. “She must be pretty,” he said, and breathed fumes into my face. His hands shaped an hourglass in the air between us.

If he wanted to think that, fine. Then he wouldn’t think about Big Stu. I told a few lies—you know the kind I mean. That grin got wider on his country-boy mug. He smelled like a brewery. I think he’d be our ace for real if he didn’t drink so much. I had to hope he’d recall my news.

A blue jay on the chain-link fence around the mill screeched at me when I came out. Behind the fence, that damn zombie—or maybe it was another one; I don’t know—was rolling a barrel of flour to a truck. He wasn’t going real fast, but he was going. He’d keep going all night long, too. Why not? It wasn’t like he’d get tired. Or hungry.

I was getting hungry. Back at the shack I had half a loaf of bread going stale and some beans I could boil up. I’ll never make a cook, not if I live to be a hundred. So I headed to Big Stu’s again, to spend his money in his joint. I don’t know if the barbecue is as good as the stew, but it’s plenty good enough.

“Live here, do you?” Lil said.

I kind of grunted and let that one alone. It’s one of those jokes that would be funny if only it were funny, you know? Big Stu’s was an awful lot nicer than were I did live. If it had a bed, I wouldn’t’ve half minded staying there all the time. Then he could’ve found even more ways to land me in trouble.

I ate up the barbecue. Since I had that ten-spot and the promise of more, I ate a slice of apple pie with cheese on top, too. I left Lil a dime for a tip—when I’ve got money, nobody can call me a cheapskate. By that time, it was getting dark outside. I let out a long, long sigh, got up, and went on home.

* * *

Be it ever so humble… I know you’ve heard the old chestnut. You want to know what I think, that’s a pile of crap, too. If somebody’d burned down the shack I lived in, he would’ve done me a favor.

It was on the outskirts of Enid, where the town turns into farm country without quite knowing it’s doing that. My pa, he lit out for California year before last. A carpet came by heading west, he hopped on, and he was out of there. He took all the money in the place, too. Seven dollars and some-odd cents, I think it was.

Can’t say I miss him much. We didn’t get along while he was here, which is putting it mildly. No note or anything to tell me where he’d gone—he doesn’t have his letters. The old lady across the street let me know the next day. I was doing something or other for Big Stu, so I wasn’t around when he hightailed it.

Hell, if I had been I might’ve gone with him. Then this’d be a different story. I can’t say how, but different for sure.

It’d be a different story if my ma were still around, too. I just barely remember her. I was five, I guess, and I was all excited on account of I was gonna have a new baby brother or sister. He would’ve been a brother if he’d lived. That’s what Pa told me. Only he didn’t, and neither did Ma.

So it was Pa and me, and then it was only me. I went back to the place to sleep, and to eat when I couldn’t afford Big Stu’s or one of the other joints, and that was about it. Some guys on their own make pretty fair housekeepers. Not me. Pa used to say I could burn water when I boiled it. I won’t tell you he was wrong, exactly, but I will say he was one to talk.

When I got inside, I lit a kerosene lantern. That let me find my beatup old cardboard suitcase. It’s longer and thinner than most, so it’ll hold a couple-three bats. I put them in—two Louisville Sluggers, one Adirondack—and my spikes and my glove, and the gray flannel uniform with ENID EAGLES across the shirtfront in red fancy letters. Then I put in some ordinary clothes, too.

And, since I was supposed to send this Mitch Carstairs a message, I dropped a blackjack and some brass knucks into the suitcase. Big Stu’s plan looked pretty good to me—get in the first lick and make it count. They’d help. Where’d I get ’em? You do things for Big Stu, you get stuff like that, just in case. I hadn’t used ’em much before, but I had ’em.

Across the road, the old gal who’d told me Pa’d headed west had the radio on so loud I could hear Amos ’n’ Andy inside my place. She’s deaf as a brick. She had power in her house, though. We never did. If we had, they would’ve shut it off ’cause we couldn’t pay the bill.

Power. I laughed, not that that was real funny, either. With any kind of power, I would’ve been good enough to play pro ball, maybe claw my way up to the bigs, even. I can run. I can catch. I can throw. You play center field, you’ve got to be able to do those things. But my hitting’s on the puny side. Always has been, dammit. I went to a tryout for the Dallas Steers once. Soon as they saw me with a bat in my hands, they said, “Sorry, sonny,” patted me on the head, and sent me on my way. They reckoned they could find better.

Worst of it is, they were right.

After I packed, I didn’t have a thing to do till I caught the bus for Ponca City the next morning. I carried the lantern into my room, blew it out, and went to bed. I could still hear Amos ’n’ Andy from across the street. I didn’t care. With a full belly and a little cash, I didn’t care about anything, no more than a dog would. You’re poor enough, life gets pretty simple.

* * *

I ate stale bread for breakfast instead of coughing up another quarter at the diner. Then I lugged my sorry suitcase to the Red Ball Bus Lines station on East Maple. The bus wouldn’t set out for another hour and a half after I got there, but I could do nothing at the station as well as I could at home.

Better, even. They set out newspapers in the waiting room—today’s Enid Morning News and the Tulsa Tribune from day before yesterday. Pa didn’t know how to read and write, but I do. I’m glad I do. It’s handy and it kills time, both. I grabbed the Tribune. It had a funny page, and the Morning News didn’t.

The hour and a half turned into two and a half—the bus came late. I was ticked but not surprised; Red Ball did things like that. The Tribune had a story about a king—or maybe he was just a minister—way on the other side of the ocean who promised he’d make everything run on time. Big Stu would’ve bet against him, I expect.

A guy who looked like a drummer and another one who looked like he’d maybe be a werewolf at full-moon time got off the bus when it finally did chug in. Me and a colored fella, we climbed on. He went to the back. I sat a couple of rows behind the driver. The bus wasn’t anywhere close to crowded.

For twenty miles north from Enid, US 81 and US 60 are the same road. Then 81 goes north into Kansas; 60 swings east. The road wasn’t close to crowded, either. A few trucks, a few flivvers, us. A few carpets overhead. Costs about the same to ship by magic or by wheels. If it didn’t, one would run the other out of business.

Kids played baseball in the fields by the highway. A lot of ’em should’ve been in school, but they played anyhow. I never did any such thing—and if you buy that, I’ll tell you another one. White kids, colored kids, Injun kids, they all just played, together and separate. They’d sort out the rules of how things worked when they got bigger. I must’ve seen half a dozen games by the time 60 forked off 81. There’s Pond Creek and Lamont—little, no-account places—and then, eventually, there’s Ponca City. It’s about sixty miles from Enid. It only felt like forever ’cause the bus went so slow and stopped at every other farmhouse, seemed like.

Halfway between Pond Creek and Lamont, it stopped in the middle of nowhere. Driver said something that made a lady cluck like a laying hen. I leaned out into the aisle to look through the windshield. A load of rocks was spilled across the highway, and a carpet down beside it on the verge. The only way the wizard on that carpet could’ve looked glummer was if the rocks had smashed a car and the folks in it. Drunk or just sloppy, he’d fouled up his spell some kind of way.

We wouldn’t make it to Ponca City or even Lamont till those rocks got cleared. We all piled out of the bus—even the lady who’d clucked— and started shoving. The unhappy wizard helped some, too. So did a family in a Hupmobile. A couple of farmers brought their mules.

The clucking lady wagged a finger in the wizard’s face. “Your company will pay for this!” she said, all angry.

“I am my company,” he answered.

“Then you will,” she said, which sure didn’t turn him any more cheerful.

I wasn’t what you’d call happy, either. I muttered some ungodly things while I hauled rocks. Just what I’d need, to mash a foot so I couldn’t run or smash a finger so I couldn’t throw or hold a bat—or swing a good right at Mitch Carstairs.

But my luck stayed in. I didn’t hurt myself; I didn’t even rip my pants. We finally cleared a path wide enough for the bus to sneak through. The passengers climbed aboard. The family got back into their car. The farmers took the mules away. And the damnfool wizard just sat there on his carpet with his head in his hands like he’d dropped the last out in the bottom of the ninth and cost his team the game. I know that feeling—I wish I didn’t. It’s not a good one.

We left Enid late. We had trouble on the road. So we got to the Ponca City bus station later than late. One guy in there waiting for the bus. Oh, he was hopping mad! He cussed worse’n I did shifting those rocks, and a lot louder. It didn’t do him any good, mind, but he was too steamed to care.

I carried my suitcase to the roominghouse where the Eagles stay when they come to Ponca City. It was only a few blocks from the one where Charlie Carstairs’s kid brother was staying, so that was handy. I’d made up some song and dance about why I was in town a day ahead of the rest of the team, but I turned out not to need it. Soon as the landlady—widow woman—saw who I was, she nodded and said, “Heard you were comin’ early. I’ll put you in Seven tonight.”

Heard from who? I wondered. But I didn’t need to be Hercule Sherlock or whatever his name is to cipher that out. Big Stu knows folks all over Oklahoma—into Kansas and Texas and maybe Arkansas, too. One of ’em must’ve put a flea in her ear.

Room 7 was a lot less crowded than it would be with four or five of us in there like usual. I picked the bed with the mattress that was less swaybacked. With luck, I’d get to keep it—well, half of it—when the rest of the Eagles came up from Enid.

You stay at a rooming house, you have supper with the rest of the lodgers. That’s part of the bill. Not a fancy supper, or they’d charge more. I wasn’t fancy. Where else would I go? Ponca City didn’t have a diner anywhere near as good as Big Stu’s. One of the gals at the table—a secretary or something, I guessed—looked nice. Not I want to run off to the Sandwich Islands with you, sweetie nice, but enough to keep my mind off the pinto-bean soup and tinned peas boiled all gray.

She didn’t even notice me—she had eyes for one of the other fellows. So I finished eating, I put my dishes in the sink like a good boy, and I went back to my room. Nothing much to do in there, so I did nothing for a while. Not like I didn’t have practice doing nothing back at the shack.

* * *

Must’ve been about nine o’clock when I cinched my belt a notch tighter. Then I put the knuckleduster in one front pocket of my trousers and the blackjack in the other. I walked around in there a bit to make sure the pants stayed up all right. They were fine, so I slipped out of my room, out of my roominghouse, and over toward the one where Mitch Carstairs stayed.

Good thing it wasn’t far. I didn’t know my way around Ponca City real well, and it was dark as the inside of a zombie’s brain out there. I wore a cross around my neck to fight off the vampires, but having faith helps, too. I wasn’t feeling what you’d call faithful just then, not with the job I had ahead of me.

I might’ve walked right past the place if a car hadn’t picked that second to turn. The headlight beams speared out and lit up the brass numbers—527—on the building. It was yellow brick, two stories high: bigger than the roominghouse where I was.

When I tried the front door, it opened. I figured it would. People still come and go at that hour. More brass numbers over the doorways showed which room was which. I slipped down the hall, quiet as I could, till I got to 13.

Light leaked out under the bottom of the door. That made me let out a sigh of relief—he was home. What would I have done if he’d decided to spend the night playing bridge with his buddies? Wait in the bushes till he came back? I’d had notions I liked better. It was dark out there, and I wasn’t sure I’d recognize him at high noon. I mean, I knew what Charlie Carstairs looked like, but I didn’t have any promise Mitch looked the same way. Big Stu should’ve given me a picture. I should’ve thought to ask for one back in Enid.

But I didn’t have to worry about any of that now. I slipped my right hand into the brass knucks. I made a fist in my pocket while I knocked on the door with my left hand.

Somebody moved in the room. I could hear it over my pounding heart—no, I wasn’t used to the rough stuff. This was worse than facing a wild fireballer with the bases loaded and the team down two in the late innings.

The door opened, it seemed like in slow motion. Yeah, I was that tensed up. Only I couldn’t haul off and coldcock the first thing I saw on the other side. If something had got fouled up some kind of way, if it wasn’t Charlie Carstairs’s brother, I’d feel bad about whaling the snot out of the wrong guy. Big Stu probably wouldn’t pay me the ninety he still owed me, either. Odds were he’d take the first ten out of my hide.

Then the door got all the way open. I started to ask, You Mitch Carstairs? As soon as the guy in the room went Yeah or Uh-huh or Who wants to know?, I’d let him have it.

Only I couldn’t. Even the question clogged in my throat. Because it wasn’t a guy in the room. It was a girl.

She was somewhere near my age. Dark blond hair in a permanent wave, green eyes, pert nose. Prettier than the secretary-type gal back at my roominghouse. Not actress pretty, I guess, but not far from it. “Yes?” she said to me, her voice deep for a girl’s.

God damn Big Stu to hell and gone! He didn’t say anything about a girl. She complicated everything—in spades, she did. But I needed that money the way I needed air to breathe. So instead of what I’d meant to ask, I came out with, “Where’s Mitch Carstairs?”

Those green eyes got a little wider. “I’m Mich Carstairs. I don’t think I know you.”

I felt like she’d sucker-punched me, not the other way around. And I realized I hadn’t even known what I was doing yet when I swore at Big Stu in my head before. He’d had a magic done, looking for Charlie Carstairs’s kid brother, and the wizard said Michelle and he heard Mitchell. Or maybe the wizard screwed it up. I didn’t know, and I still don’t.

But I did know that, no matter how bad I needed those ninety clams, I didn’t need ’em bad enough to beat up a dame to get ’em. I’m no vampire—I have to be able to look at myself in the mirror. I couldn’t do what Big Stu wanted done, not if my life depended on it. That I might be laying my life on the line by not doing it… I didn’t think about that, not then. Fool that I was.

Real fast, I said, “No, Miss, you don’t know me. But you’re Charlie Carstairs’s sister, aren’t you? Charlie Carstairs over in Enid?”

“That’s right.” She gave kind of an automatic nod. “Has something happened to—?” She broke off.

“He’s fine—now. So are you—now. If you stick around Ponca City for even another day, though, you won’t be.” Once Big Stu found out I’d messed up, he’d send some guys who didn’t worry about what they hit as long as they got paid. Still fast, I went on, “Get out of town. Get out of state. Go to California.” Yes, I had Pa in my head. “Just go, quick as you can. Git!” I might’ve been shooing a stray dog.

Her eyes got wide again, wider this time. “I can’t do that!”

“Sister, you can’t do anything else, not if you want to stay in one piece. I know what I’m talking about.” I pulled out my right hand with the knuckleduster still on it. If I’d tried to take the damn thing off, it would’ve looked like I was playing pocket pool. She saw what it was, of course, but she didn’t raise any fuss. She must’ve seen I wasn’t about to use it. After I stuck it back in my pocket, I said, “Yeah, I know, all right. Some pieces of work, you just can’t do.”

“Thank you,” she said quietly. Her mouth twisted. You want to know how pretty she was? She was still pretty when it did, that’s how pretty. For all I know, she might’ve got even prettier. When her face cleared, she nodded once more, this time to herself and not to me. “All right. I’ll be gone tomorrow. I don’t know where. I don’t know what I’ll do. I haven’t got much money, but—”

“Neither do I,” I stuck in. “Why d’you reckon I came up here?”

“Thank you,” she said again, even softer this time. Then she closed the door on me: not slammed it, but closed it. I didn’t mind. We’d already said everything we had to say to each other, hadn’t we?

I got the hell out of there. I hoped she got the hell out of there, got the hell out of Oklahoma, come morning. Well, I’d done everything I knew how to do. If it wasn’t what Big Stu wanted… I was almost to the roominghouse front door when I really and truly realized I’d just crossed the guy who ran a lot more of my home town than the mayor ever did.

The door opened. A man—I guessed he was one of the lodgers— came in. He was skinny and sad-looking, with worn clothes and gray hair getting thin at the front. He could’ve been anybody. He paid me no special mind—I could’ve been anybody, too. Some other lodger’s friend, or maybe a new lodger he hadn’t met yet.

Only I wasn’t anybody, not any more, or not just anybody. I was somebody dumb enough to get Big Stu pissed off at him. In Enid, you couldn’t get much dumber than that. Big Stu’d wanted to hurt Charlie Carstairs through his kid brother, only she turned out to be Charlie’s sister. He couldn’t hurt me through anybody else. Everyone I might’ve cared about was either dead or gone. No, he’d have to pay me back in person.

All of a sudden, what I’d told Mich Carstairs looked like pretty good advice for me to take, too. The farther away from Big Stu I got, the better off I’d be. If I had any smarts, I’d hitch a ride or hop a freight or jump on a carpet the way my old man did. If I had any smarts, I’d do it tonight. I wouldn’t wait for sunup. The sooner, the better.

But I didn’t have any smarts. What I had was a game tomorrow. I couldn’t let the other Eagles down, not even on account of Big Stu. Hal Snodgrass, our backup outfielder, he was slower’n an armadillo after it meets a Model A.

I almost hoped a vampire would try to jump me while I walked back to my boarding house. Maybe I’d fight him off and work out some of what I was feeling. Or maybe he’d get me and turn me into something like him. Then I wouldn’t care about anything past my next drink of blood—cow or sheep or coyote blood, or maybe I’d go after people, too, if I was bold.

No vampires, though. Nothing but the stars shining out of a clear, dark sky. The air was cool, close to crisp. Pretty soon it would get hot and sticky and stay that way for months, but that hadn’t happened yet. The skeeters hadn’t come out, either. Without so much on my mind, I might’ve enjoyed the walk.

My landlady hadn’t locked the front door. I’d timed it all fine— about the only thing I’d done right since I got to Ponca City. I went to my room, laid myself down, and tried to sleep. Took a while, but I did it. I don’t remember the dreams I had. I do remember they were the kind you’d want to forget.

II

We would play the Greasemen at half past two. We had to make sure we could get the game in before dark. They were already starting to play under the lights even back then. It was risky, though. You really have to tame salamanders or electrics before they get along with wooden stands. So I’d heard of night games, but I’d never seen one and I’d sure never played in one.

Not then, I hadn’t. Been some changes made since.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The widow woman’s breakfast was as grim and cheap as her supper. Still and all, you can fill your belly on bread. I’d done it often enough in Enid. The bad, bad times come when you haven’t got enough bread or anything else to fill up your empty.

I went down to the room at the end of the hall and took a bath after the folks there who had regular jobs headed off to do ’em. Didn’t have to hustle so much that way. Other people weren’t pounding on the door and yelling for me to hurry up in the name of the Lord.

I was slicking down my hair and combing a part into it at the mirror on the chest of drawers in my room when I heard a commotion in the front entryway. I knew what that had to be, and it was. The rest of the Enid Eagles had made it to Ponca City.

They all whooped when I came out to say hello. Ace McGinty must’ve been running his mouth but good. “Hope you’re not too tuckered out to play today!” he called to me.

“Ah, stick it,” I told him.

Which was the wrong thing to say, of course. “I thought that’s what you were doing,” Mudfoot Williams said. He was our third baseman. His name was Zebulon, but he’d been Mudfoot since he was a kid. He hated shoes more’n anything, and went barefoot whenever he could.

Him and Lightning Bug Kelly (who always had a smoke going, even when he was catching) and Don Patterson, our top pitcher, threw their bags into the room with me. The other guys got their rooms. Nobody stayed in ’em long, though. We put on our baseball togs, grabbed our gloves and shillelaghs, and headed on over to Conoco Ball Park.

It’s on the southwest edge of town, over by US 60. The diamond in Blaine Park is better kept up, but all of the Greasemen except a couple of ringers work in the oilfields, so they play on the company field. We got there a couple of hours before game time, but a few people were already in the stands. Not one whole hell of a lot to do in Ponca City. Well, Enid’s the same way.

Rod Graver played short for us, and managed, too. He was about thirty then, not slick, but steady, which you need if you’re gonna ride herd on a bunch of ballplayers. He’d got up to B ball in the pros. He might’ve gone further, but his brother hurt himself and he had to come back and take over the farm work.

Him and me, we threw a ball back and forth to loosen up. After a few minutes, he came over and asked, “You do what you needed to yesterday?” He talked low, but he knew I hadn’t come to Ponca City early so I could dip my wick. That meant he talked to Big Stu. It meant Big Stu talked to him, too.

I’ve always made a lousy liar. I shrugged back at him. “You tend to your business and I’ll tend to mine,” I answered, not sharp—I didn’t want to quarrel before the game—but giving away as little as I could.

He got a double furrow, up and down, above his nose. His eyebrows pulled down and together. “Big Stu won’t fancy that,” he said, his voice as flat as you wish infield dirt would be.

“Big Stu’ll just have to lump it,” I said. “I’ll pay back the down payment—he doesn’t need to fret over that.” I hoped I’d get ten bucks from my share of the gate today. If I didn’t, well, I’d come up with the rest some way or the other.

Not that that’d do me much good, not with Big Stu. I didn’t do what he told me to, so I was dirt to him from then on out. Not dirt—manure. I knew it. So did Rod. He clicked his tongue between his teeth. “Jack—” he started, and stopped right there.

“It’s done. I mean, it’s not done. The hell with it. The hell with everything,” I said. “Let’s play ball.”

He turned away. Let’s play ball would do for that day, and maybe for the next one. It sure wouldn’t do once I got back to Enid. Like the Mitch Carstairs who hadn’t been there, I’d be an accident waiting to happen, and I wouldn’t wait long. I hoped the Mich Carstairs who had been there was somewhere a long ways away by then. I wondered what I would’ve done if she’d been mud-fence ugly. Lucky—I guess lucky—I hadn’t needed to worry about that. Anybody who tells you looks don’t count in this old world, he’s talking out his rear end.

The Greasemen got to the park right after we did and started warming up alongside us. Their home whites had Greasemen across the chest in script, and CONOCO underneath in smaller printed capitals so you could see who they worked for. They razzed us, and we razzed them right back. We were the two best teams in north central Oklahoma, and we both knew it.

People kept filing into the ballpark. Looked like we’d draw 1,500, maybe even 2,000. A quarter a pop, half a buck to sit right back of home, and that’s a decent gate. Road team—us—would split forty percent of it. Some money for everybody, but they call it semipro ball ’cause you can’t make a living on it.

Two umps, just like in the little pro leagues that pop up in these parts and then die like your crops in a drought. Guy behind the plate was local; guy on the bases drove up from Enid. They’d switch when the Greasemen called on us. I’d seen both of them often enough before. They mostly didn’t screw the team from the other side too hard.

“Batter up!” yelled the plate umpire. He was already sweating in his black suit and mask and protector. The crowd whooped and stomped. They were rooting for the Greasemen, except for the few who’d come over from Enid.

Ponca City pitcher was a big redheaded right-hander named Walt Edwards. He’d played pro ball till a sore soupbone sent him back to the oil works. Though he couldn’t throw hard any more, he knew what he was doing out there. His fastball might not break a windowpane, but he could drive nails with his curve.

Our leadoff man hit back to the box. Then Mudfoot touched Edwards for a single to left, but he didn’t get any farther. Don Patterson took the hill for the bottom of the first. He was the opposite of Walt every which way ’cept they were both tall. He was a lefty, and he could fire the pill through a brick wall. Trouble was, about one game in three he couldn’t hit a brick wall with the damn thing.

Conoco Ball Park’s got a center field like they say the Cricket Grounds does—it goes on and on. I played deep, too. I knew I might have to cut across. Our guys in left and right weren’t what you’d call swift. Even from way out there, the ball went pop! every time it slammed Lightning Bug’s mitt.

Don walked their second hitter, and the next guy blooped a Texas League single in front of me. But we turned a slick double play on their cleanup man—told you Rod’s smooth—so we got out of it.

I was up second in the second. I waited on one knee in the on-deck circle, watching Edwards work. It would’ve been a pleasure if he hadn’t been pitching against us. You need to think on the mound. If you can’t blow it by somebody, you need it twice as much. He could do it. Oh, couldn’t he just!

Our first man up grounded to short. I stepped into the batter’s box. Ponca City fans booed me. They booed everybody in an Enid uniform, so I didn’t think anything of it. Edwards threw me a curve just off the outside corner—I thought. The plate ump’s hand went up. “Stee-rike!”

“You missed that one,” I said. I didn’t turn my head toward him. The crowd would’ve got on me, and he would’ve thought I was showing him up. Then my strike zone would’ve been as wide as Big Stu the rest of the day.

“You hit. I’ll umpire,” he said, which didn’t leave me much of a comeback. So I dug in and waited for the next one.

I guessed right. It was another slow curve, only inside this time. I bunted it down the third-base line and beat it out easy. “That’s crap,” said their first basemen as I took my lead. His name was Mort Milligan. He had arms and shoulders like a blacksmith and he looked mean, so I didn’t sass him back. I just grinned.

Lightning Bug swung from the heels and popped up. Our next guy struck out and left me stranded. I trotted to center, picked up my glove—you leave ’em out there when your side hits—and I was ready.

This frame, Don walked their first guy. Then that hulking first baseman came up. Milligan batted left, so I slid a step or two into right-center, just in case. He swung through the first pitch. The next one was a foot off the plate—he let it go by. Don looked in at Lightning Bug, nodded, rared back, and let fly again. This time, the Greaseman connected.

You hear that crack! off the bat like a rifle, you start running. You worry about how far later. As far as you can is a pretty good bet. You hear that crack!, even as far as you can may not come close to far enough.

If I hadn’t shifted those couple of steps toward right, I never would’ve had a prayer. I didn’t think I had one, anyway. I was running hard as I knew how, but the ball roared out there like a freight on a long downgrade. If it got by me, the man on first would score for sure. Only thing that might hold Milligan to a triple was him being strong and slow. Might. You put a ball over the center fielder’s head in that park, you can run for days.

At the last possible second, I threw out my arm. I will be damned if the ball didn’t land square in the pocket and stick. They tell you not to catch one-handed, ’cause it’s too likely to pop out. You want to say I got lucky, I won’t argue with you.

By that time, Mort Milligan was past first. The runner on first was halfway to third—he’d taken off at the crack of the bat. My throw in hit the second baseman. He’d gone out to short right, figuring I’d be flinging from the fence. His relay doubled off the runner easy as you please.

The crowd went nuts. They don’t often cheer the visitors, but I got a heck of a hand if I do say so myself. Mort Milligan pointed out at me like I’d picked his pocket. “You son of a bitch!” he shouted. I just stood there, waiting to see if we’d get the third out.

We did. I came into the dugout. They clapped for me again. One guy tossed me half a buck, and another a silver cartwheel. I touched the brim of my cap to both of ’em. I always needed money, and right then more than usual.

Well, I won’t give you the whole game like a radio fellow. We beat ’em—the final was 5-3. I didn’t get any more hits. I did catch the last out. It was a can of corn, as high and lazy a fly ball as you’d ever want to see. Your granny could’ve put it away without a glove. I caught it with both hands just the same.

When I brought in the ball, Milligan shook his head at me and said, “You wouldn’t make that play again in a year of Sundays.”

“I made it this time,” I answered. Then, because we’d won, I needled him back: “You won’t hit it that hard any time soon, either.” He gave me a dirty look, but he turned away.

One of the men in the crowd, an old fellow with store-bought teeth, threw me another silver dollar, which I didn’t even slightly expect. He said, “I’ve been playing and watching since before they wore gloves, and that’s as good a catch as I ever seen.”

“Obliged, friend,” I told him, and I meant it more ways than he knew. I felt pretty darn proud—as proud as a guy can feel when he doesn’t dare go home with the rest of the team after the game.

Rod Graver was under the grandstand with the Ponca City manager, splitting up the take. More stacks of quarters than you can shake a stick at. Once everything got figured out, my share would be somewhere north of ten bucks—it had been a good house. I’d be glad to have it. I would’ve been gladder yet if it’d been more.

Most of the Eagles didn’t know I had things on my mind. Don Patterson pounded me on the back—almost knocked me over—and said, “Thanks, Jack. You saved my bacon out there.”

I wondered who would save mine. I wondered if anybody would, or could. All I said was, “Any old time. Part of the service.” Don laughed and laughed. His only worry was slathering liniment on his arm once he went back to the roominghouse.

We got paid at the ballpark. Rod gave everybody a roll of quarters and then a dozen more besides. “Thirteen dollars,” he said, in case we couldn’t work it out for ourselves. That was about what I thought, all right. He kept some extra for himself, on account of he was the manager and did more for the team than just play ball. I don’t know exactly how much of a bonus he took. I do know you couldn’t’ve paid me enough to try to keep a bunch of roughnecks like us all heading the same way.

We felt proud of ourselves when we rode back to the roominghouse. You always do when you win, and especially when you win on the road. Win on the road and even 3.2 beer tastes good.

* * *

My roomies joined the crowd at the end of the hall to take their turns in the bathtub. Pretty soon, they’d have the choice between dirty bathwater and cold. Since I’d gone in there that morning, I figured I could let it slip. I got out of my uniform and into my street clothes.

Silver clinked, all nice and sweet, when I moved it from the back pocket of my baseball pants to the front pocket of my regular trousers. The quarters, the half, the heavy dollars… I smiled. Money does make things better.

I hefted the roll of quarters Rod gave me. It made almost as good a fist-packer as the brass knucks I hadn’t used. Then I frowned and hefted it again. I know what a roll of quarters weighs. I’d better—I’ve got ’em at enough different ballparks. This one didn’t feel quite right. I peeled off some of the orange paper wrapper.

Slugs spilled into the palm of my other hand.

“Well, shit,” I muttered, there where nobody could hear me. So it had started already. Ten bucks can take you a ways. Not having it would be bad. Not having it when I thought I did would’ve been worse.

I went next door to Rod’s room. When I knocked, he opened it himself. Made things simpler. “Need to talk to you a minute,” I said.

“Sure,” he answered, like nothing was wrong. I told you before— Rod’s smooth. “What’s going on?”

I jerked my head toward the front door. He came with me, easy as you please. When we got outside, I flipped him one of the slugs. “Pay me for the game,” I said.

It didn’t faze him a bit. He caught the slug—he has good hands— and stuck it in his own pocket. “You told me you’d give back the ten you got out of Big Stu,” he said.

“That’s between me and him. It’s got nothing to do with you,” I answered. “Pay me for the goddamn game. Pay me for the catch. Pay me or I’ll go back in there and show the guys what you tried to pay me with.”

That hit him like one of Don’s fastballs in the ribs. If the Eagles found out he’d stiffed me, most of ’em—maybe all of ’em—would be on my side. Semipro teams break up all the time. Something like that could be plenty to break up the one he ran.

He was smart enough to see as much. He never was a fool, Rod Graver. “Okay, Jack. Keep your shirt on,” he said, which couldn’t mean anything but Keep your trap shut. He hauled out his billfold and gave me two fives. “Here you go. You happy?”

“Happy like snow is black,” I said. Little old Jew ran the hockshop in Enid I knew too well. I got that one from him.

Rod just looked at me. I bet he was never in a hockshop in all his born days. He said, “If you think ten bucks’ll keep you away from Big Stu longer’n ten minutes, you better do some more thinkin’.”

“Nuts to that.” I didn’t want him to see he’d hit a nerve. “I sweat for that money out at the ballyard. I ran for it. It’s mine.”

“It’s yours now,” he allowed, “but you better keep runnin’.”

“Don’t worry about me. Worry about how you’re gonna find another center fielder. The guys you got now, they’d have to play it on a bicycle.”

He smiled then, just a hair’s worth. “Bicycles,” he muttered. “Luck to you, you dumb bastard. Anybody who gets in bad with Big Stu is a dumb bastard, but luck to you anyways. You’ll need it.”

I wanted to ask him how come he was doing Big Stu’s bidding. But you don’t need to ask a question like that. You only need to think of it, and it answers itself. Rod did things for Big Stu ’cause he knew which side his bread was buttered on, that was how come.

* * *

We walked back into the roominghouse together, like nothing was wrong. A little while later, most of the Eagles went out to dinner. Ponca City may not’ve had a good diner, but it had a chop-suey house, which Enid didn’t. Me, I ate another roominghouse supper at the widow woman’s sorry table. I didn’t want to spend a quarter or half a dollar, not when I was about to pull up stakes. And I wouldn’t’ve been good company for the other fellas, either. They wanted to celebrate beating the Greasemen. I didn’t have anything to celebrate about.

All three of the guys I shared the room with went out to eat. When I said I didn’t feel like it, Don offered to buy for me. “Least I can do after you went ballhawking for me like that,” he said.

“It’s not the money,” I lied—it was, some. “I don’t feel like it, is all.”

He could tell I wasn’t saying everything I might have. Lightning Bug and Mudfoot dragged him out before he had the chance to get snoopy, though. After I had my supper, such as it was, I went out for a walk. It was heading toward dark, but it hadn’t quite got there yet. Maybe the folks at the roominghouse thought I wanted a constitutional to settle myself after the game. That’s just my guess—I didn’t ask ’em, since I didn’t much care. Any which way, I went, and I was glad to be gone.

I wasn’t going back to Enid; I knew that much. A mouse doesn’t turn around and run straight into the cat’s mouth. All I had in Ponca City was in my pockets or in my suitcase or in my head. I could do ’most any kind of odd job, if anybody’d hire me. But things in Ponca City were as rough as they were in Enid or anywhere else. I was a stranger in town, too. Nobody knew me from a hole in the ground.

I chuckled under my breath while I walked along. That wasn’t so. The Greasemen knew me, all right, and better than they wanted to. About the only thing I could do better than most fellows my age was play center field. I couldn’t do it that much better than the fellow they already had, though. They wouldn’t cut him loose so they could take me on.

The one thing I was good at, I wasn’t good enough at to do anything with it. Sure looked that way to me then, anyhow. You never know what’s comin’ round the corner till it smacks you in the chops.

Me, I came round the corner and found myself on Palm Street, a block and a half from the boarding house where Mich Carstairs had been staying. My feet knew where they were going even if my head hadn’t a clue. Or maybe my head did know, but decided not to say anything for a while.

When I got to the boarding house, I paused in front of the door, listening. I didn’t want to go in if they were still eating in there. Then I wondered why the devil not. What difference did it make tonight? I wasn’t going to do anything bad. That had been the night before, and look what it got me.

So I turned the knob and walked inside. A couple of men did sit in the dining room, smoking and shooting the breeze. One of them was the beat-down-looking older fellow I’d passed on my way out before. I nodded to him to show I remembered, and he gave it back. Then I went on down the hall.

No light under the door from room 13 now. Well, that didn’t have to mean anything. I knocked, waited, and knocked again. Nothing but quiet on the other side of the door. Oh, maybe she was at a picture show. But maybe she’d listened to me after all. I could hope so—I could, and I did.

Out I went. I got another nod—a suspicious one this time, I thought—from that gray-haired guy. If he never saw me again, it wouldn’t break his heart. If I never saw that boarding house again, it wouldn’t’ve broken mine. And I never did. I’ve had my heart broken a few times since—life is like that. But the boarding house had nothing to do with any of ’em.

It was full dark, dark dark, by the time I left. I was heading back to the place where the Eagles stayed when a voice spoke to me out of the night: “Hey, buddy, wanna take all your troubles away?”

If that voice sounded like it belonged to a pretty girl, I bet I would’ve gone with her. Chances are I would’ve spent my cash and got up with more troubles than I’d lain down with. It didn’t, though. It was a man’s voice, a colored man’s, deep and smooth and buttery. He didn’t seem to want to knock me over the head or anything. No, he had the kind of voice that could’ve sold sand in the desert.

“What are you talking about?” I asked him—that’s how smooth and slick he was. I knew better. Nobody who calls to you like that is out to do you a favor. He’s out to do himself one. I understood that. I answered all the same.

“I work for a conjure man,” he said, and I bet he did. Maybe that was how come he sounded so good—his voice could’ve had a little spell on it. He went on, “Let me take you to him. The way you’re stompin’ along, I can tell somebody done you wrong. Once my master gets done, though, he’ll fix you up so you never care about nothin’ like that again.”

I didn’t know I’d been stomping along. For all I can say, I hadn’t been, and he was just spinning out a line like a spider to see if I stuck. But after that I wasn’t stomping, and I know that for sure. I was running, running harder than when I chased down the liner that musclebound first baseman tagged. When the colored fella said fix you up, he meant turn you into a zombie. I sure wouldn’t care about anything after that. Being a zombie’s worse than dying and going to hell. Looks like that to me, anyway. When you go to hell, at least you know why. Zombies don’t—can’t—know. That’s what makes ’em zombies.

Where would I have wound up? On a farm out West, pulling beets out of the ground forever? More likely at the Conoco works, rolling oil barrels around the way that zombie at the mill in Enid rolled flour barrels. One of the Greasemen might’ve seen me and laughed.

I tried to cock my head while I ran, so I could hear if the colored fella was gaining. He wasn’t—he wasn’t even chasing me. The bastard didn’t need to bother. Way things are since the Big Bubble busted, getting rid of all your worries looks pretty damn good to more and more folks. Who cares what you do afterwards? You sure won’t.

No, the conjure man’s helper didn’t need me. He’d find somebody else instead, somebody desperate enough to be glad to go with him. Then he’d be happy, and his boss would be happy, and Conoco would be happy, too. Everybody’d be happy—except for the somebody else. He’d be a zombie, sorrier than damned.

I had just slowed down from my wild run to a walk when a vampire jumped out at me from behind a parked Willys. Fry me for a catfish if I can tell you what the police and magic patrol were doing that night. Not keeping an eye on the streets between those two rooming houses—I can tell you that. Twice in a couple of blocks! I might as well’ve been in New York City, not Ponca City.

“Give me your blood!” the vampire said when he reached out for me. He talked the same way I did—none of that mush-mouthed foreign stuff. So he couldn’t’ve been one of the ones who brought being a vampire to the States from the other side of the ocean. He’d been an ordinary Joe till one of them or one of the ones they got got him.

Which didn’t mean I fancied his fangs punching into my neck. I whipped out my cross, quick as I could, and stuck it in his face. The cross flared, bright like a welding torch. I’d had to use it once or twice before, but I’d never seen it do anything like that. I must’ve had a lot more faith than usual, I guess because I was just thinking about zombies and hell and all.

“Arrh!” The vampire flinched away from the shining cross.

“Go kill a cow if you need blood that bad,” I said.

He made a horrible face. “I’ve been doing that too damn long. It’s like eating grits without butter or salt all the time. I want something with some taste to it.”

“Well, you can’t have me. Go on, git, or I’ll make you sorry.” I eyed him. He was a miserable, scraggly excuse for a vampire. He’d likely been a miserable, scraggly excuse for a man, too. “Sorrier, I mean.”

He said something Pa would’ve belted me one for if he’d heard it out of my mouth. That didn’t do him any good, either. So he slunk off, head down, in the direction I’d come from. Maybe he’d run across the conjure man’s helper. I could hope so, anyway. Could the conjure man make a vampire into a zombie? Would the vampire want him to? Could the vampire get the drop on the conjure man’s helper and drain him dry, or would the lousy bloodsucker get magicked away before he could bite? All kinds of interesting questions, and I’d never know the answers to any of them.

I came up with another one just before I got back to my rooming house. What would Rod have been telling the other Eagles about me while they were eating dinner? One more thing I didn’t know the answer to yet, but there I figured I’d find out pretty darn quick.

Worrying about that might’ve been what gave me a fit of the shakes after I went into my room. Oh, I expect running across the conjure man’s helper and the vampire within a couple of blocks of each other had a little somethin’ to do with it, too. I’d got away from them. Could I get away from what I’d done? I mean, what I hadn’t done?

I’d give it my best shot, same as I had with the Greaseman’s line drive. Maybe I’d get lucky twice. In the meantime… In the meantime, I slid under the bedclothes and tried to fall asleep. I surprised myself—I did it.

Lightning Bug and Don and Mudfoot came in a while later. Quite a while, I’d guess. They’d done some celebrating, all right. They tried to keep quiet, but when a drunk does that he only makes more noise.

“See, he’s here,” Mudfoot said. “Ace was full of it—he don’t got no girlfriend in town. He just hung around and hit the sack.”

Well, Mudfoot had it partway right. Since that was closer than he usually came, let’s leave it right there. I pulled the covers up over my head and did my best to go back to sleep. Damned if I didn’t make it, too.

* * *

“Nope.” Next morning after breakfast, I shook my head at the rest of the Eagles. “I ain’t goin’ back to Enid with y’all.”

Don looked worried. He had a heart as fine as his fastball—and about as wild. “Rod told us you might have troubles in town,” he said, and by the way he said it I would’ve bet that wasn’t all Rod said, not by a long chalk. “With us at your back, might be things wouldn’t look so bad.”

More than half the team nodded. Rod didn’t, and he didn’t look too happy that so many did. I was happy—they really did like me. That made me feel good, but nowhere good enough to go back. “Thanks, boys, but I’ll try Ponca City a while,” I said. “Nothin’ in Enid for me, and not one of you bums can tell me different.”

They kind of shuffled their feet and stared down at their shoes, but nobody tried to make me think I was wrong. Don did ask, “How come you reckon you’ll come across anything here?”

I shrugged. “Call it a change of luck. One of these days, could be you’ll see me shagging flies in a Greasemen’s uniform.”

They all shook their heads and made hex signs like the ones you use against the evil eye. Then they gathered round me and slapped me on the back and shook my hand and told me what a swell fella I was. One or two of ’em shoved money in my pocket, and it’s not like they had a whole hell of a lot more than I did.

Yeah, Rod Graver shook my hand, too. “Shall I tell Big Stu you’ve set up shop here?” he asked.

“Tell him whatever you please,” I said. “You will anyway.”

He made a face, as if to say, Hey, it’s not my fault this guy gives me my marching orders. He gives ’em to the whole town. He wasn’t exactly wrong, as I had reason to know. But he wasn’t exactly right, either. He stuck out his hand again. I took it. Why not? It wouldn’t hurt anything. Of course, it also wouldn’t help.

The old cars full of Eagles all started up, which is always a worry when you’ve got an old car. They pulled away from the curb. The guys waved till they turned the first corner and got out of sight. I stood there on the sidewalk, wondering what the dickens I’d do in a town where I knew nobody and nobody knew me.

I could stay in the roominghouse a while—it was cheap. But it’d be the first place Big Stu looked for me, so I’d best find a different one. I started walking, not going anywhere in particular but sort of heading downtown. Ponca City’s a little smaller than Enid; I wouldn’t take long to get there.

Downtown Ponca City looked like any other downtown about the same size—well, except that the city hall put me in mind of a Spansh mission dropped where one purely didn’t belong. The train station. A couple of picture houses. A hotel that looked like it needed business. A doctor’s office, and a lawyer’s, and a dentist’s, and a spectacle-maker’s. An apothecary’s shop.

Some more shops and stores. Most of them looked like they needed business, too, even though it was Saturday morning and they should’ve been jumping if they ever were. Same as you’d see in any other downtown, a good many shopfronts were closed, boarded over. You could kind of tell how long since each one went under by how many layers of flyers and posters were pasted on the boards. Some of the old paper was all raggedy, and fluttered in the breeze. Some of the posters were so new and fresh, they looked like they’d gone up right before I ambled by.

And dog my cats if they hadn’t. BALLGAME TODAY! they yelled, and underneath it was that day’s date written in by hand. The posters had a picture of two men in baseball uniforms with a big old lion’s head, mouth open and roaring, embroidered on the chest. The ballplayers looked like lions, too. They wore their hair down to their shoulders or past ’em in a mane, and they had mustaches and shaggy beards to go along.

THE HOUSE OF DANIEL! the poster said, in letters bigger even than the ones for BALLGAME TODAY! In smaller type, it went on, Today, the world-famous touring baseball team comes to your town! Be there to enjoy the show! More handwriting said they were playing the Ponca City Greasemen at the Conoco Ball Park, and that it’d cost fifty cents to get in.

The House of Daniel! I knew who they were. Any semipro ballplayer would have, and does to this day. They were the best of our bunch, like the New York Hilltoppers are in the big leagues. They’re based in a little churchy town up in Wisconsin or somewhere like that, but they barnstorm the whole country. They play the year around, too. For the winter, they head on out to the West Coast, where the weather stays good. Or they go south of the border, or take ship to the Sandwich Islands.

They beat the St. Louis Archdeacons once. They’ve barnstormed alongside big-leaguers, and had ’em on their team once they got too old to stick in the majors. They’ve played against the top colored teams, too, in places where the laws let you do that.

They aren’t part of a league or anything—never have been. So they’re semipros, just like the Enid Eagles. But they’re semipro royalty, and the Eagles… ain’t.

Funny how none of the Greasemen said anything to us about this game. Or not so funny, I guess. They didn’t want us to know, for fear we’d make our own matchup with the House of Daniel. This way, they got the bragging rights and their share of the big gate, and they left us with hind tit.

No, not us. I wasn’t an Enid Eagle any more. It hadn’t sunk in yet. I didn’t realize till that moment how much it hadn’t sunk in.

I started west and south, back toward the Conoco Ball Park. I didn’t know downtown Ponca City real well, but by gum I knew how to get to the field. I wanted to see how the Greasemen stood up against the House of Daniel, and I wanted to see those traveling hotshots go through their paces.

And… I stopped in the middle of the sidewalk, my mouth falling open. I stopped again, at the roominghouse, and stuck my spikes and glove and uniform in a sack I begged from the widow woman. If I could somehow sweet-talk the House of Daniel into taking me along with ’em, I’d go so far and so fast, Big Stu’d never catch up with me. Even if they said no, which they likely would, how was I worse off? You got to try in this old world, or nothing happens a-tall.

Excerpted from The House of Daniel © Harry Turtledove, 2016